My Alabama-born mother called my twenties “an era of discernment and Yankee wandering.”

Raised in the wide-open spaces of the languid Mississippi Delta, with expansive porches and enough two-lane highway mileage for big dreaming, I grew up believing that words and art, as vehicles to see the world, were the jet engine. They could move ideas, meaning, and reality faster than anything. As an English major, my Ole Miss education of bourbon-soaked conversations at the City Grocery in Oxford, often involving romantic analyses of Ernest Hemingway’s Havana or Walker Percy’s New York City, propelled me to seek a definition of myself that seemed somehow larger than my current surroundings in small-town Mississippi would allow.

So, I migrated to New York City to become an art dealer. It was time to leave Mississippi, a cradle of love and predictability. Despite the turmoil in New York following the 9/11 attacks, I boarded a plane in Memphis with two red, tapestry suitcases, heading for an intrinsically challenging city. It would, at times, be navigational warfare to survive and conquer.

No doubt, it was in New York where I sharpened and learned the craft of Art Dealing. Art gallery owner—and true southern gentleman—Hollis Taggart spotted me in a vintage gold coat at one of his openings and, after an instantly inspired first conversation, hired me on the spot. I let myself become fully engaged in the epitomizing New York City arts and culture scene. I spent time refining hustle and ambition, learning to understand the subtleties and sublets of art and the deals that follow. And at the other end, I found myself with a different, yet perhaps more complicated grasp on the complexities of the written word, fine art, and all that lies between.

I arrived at JFK and grabbed a cab as helicopters hovered in the Gothic skyline. I made my way to Bedford Street, a quaint tree-lined street in the West Village. My apartment was in a typical prewar building, and my room held a twin bed with a large, curtainless window that oversaw the only thing green in that part of the city: a church steeple.

The apartment was a destination off the ground entrance—a six-floor walk-up with no elevator. It had a grand mahogany door with small brass mailboxes, the keys so miniature they were hardly larger than needles. The iron stairwell had a modest décor, with lanterns that had been rewired in the ’30s but were still original to the design. The apartment offered architectural solutions for a modest space likely once lived in by immigrants. It had two airplane-sized sinks with little hot water. The makeshift shower occupied the closet. It was here that I would learn the art of modesty.

New York City was sensory overload with a new map of life on the subway. I was in constant angst over how to navigate the underground world—not just the numbered colored trains but also the filth, the crowds, and the bums, many with nondescript dogs. I was sick constantly with some kind of cold. In the first few months, I was robbed—twice.

My roommates—more like surrogate sisters—were two Mississippi gals, Sarah and Mallory. And sisters are masters at shared space, concessions, diplomatic moments, joy, and sorrow. The combination of stories and life experiences—and all that it entailed—was unique. It’s from my time in that apartment that I understand what those clichéd stories of two or three people on a raft implied about survival.

In time (a cure for so many things), I adapted to this new life with the help of my fellow Mississippians. Sarah, with strawberry hair and freckles, had a laugh as large as her heart. A voracious reader, she was skilled with words and quick-witted humor. A philosopher at heart and a thinker to be reckoned with, she was both tender and hilarious—the truest friend and the most deadly of wine drinkers. Mallory, a petite blonde with a fierce giggle, was spunky and kind and always seemed to have advice gleaned from “simple wisdom.” She rarely overthought things and was always the perfect lunch date. Sarah never had a plan, but life somehow always worked out for her. Mallory longed to marry well, have three daughters, and give them the names she had scrawled on a napkin long ago in elementary school.

It took concerted effort to make our little family thrive in such a small space. We decorated our apartment and added fresh coats of paint. We bought a trivia board and collected quarters, dimes, and nickels for laundry, tuna fish, Baked Lays, and jugs of wine. Living there was like playing ping pong, so we scheduled shower times and more. Sarah respectfully promised to go to the rooftop to smoke. Mallory needed her plugs for coffee and curlers by 7:00 a.m. I stayed up all night reading art books so preferred to sleep in until around 8:00 a.m. Gallery life didn’t start till mid-morning.

There were large windows almost floor to ceiling in every room, so we always felt connected to the heart of the village. The pedestrian conflicts or laughter seeping in through the cracked windows, buzzing cabs, and barking dogs were poetic wonderments. Sarah always said the windows helped us dream bigger and better. We had escaped the prison of small-town Mississippi. We were all on chances, hoping some type of God heard our prayers.

In time, I mastered the subway, transportation that freed and connected me to life in the West Village and to the Upper East Side, the quadrant for most high-end galleries, museums, and Hollis Taggart Galleries. With my first iPod, outfitted with white earphones, I would hop on the train and follow its “etiquette:” One never looked anyone in the eye. Artists with instruments always got seats, and so did aging men and women. One always wore deodorant and perfume inside the collar; if the smells were too strong, you could always muffle your nose in fabrics and rest your senses. Always have something to read; it could be an unpredictably long ride.

Rest was an alternative word in that city. It was there in New York that I began tweaking my craft, attending New York University to earn an art appraisal license and visiting as many museums and art exhibitions as time allowed. I also learned how to face many life and work challenges, like the type-A, cold-hearted bitches intent on climbing fast to the top, throwing knives at my back at every turn.

n the Mississippi Delta, I had known few fiercely independent and enterprising women, as most were dedicated to a more conventional life. One exception was Almyra, my tap and ballet instructor and a true go-getter, blessed with money, wealth, independence, and power. She was also wonderfully brilliant and had spent her 20s in New York as a dancer. Built like a typical dancer, she was five-foot-six and thin as a rail, strictly limiting her intake of food. Her morning “fuel” was perhaps disproportionate: one piece of toast to unlimited coffee and cigarettes. Her long fingers were always finished with bright red polish, exactly the color of her lipstick, and her rings were so big I often thought they would break her tiny bones. Her hair was so black it was a little blue, and her eyes were kind and determined. She always wore black turtlenecks and white cotton bell-bottoms to teach. She was a graceful, energetic, and kinetic masterpiece. She embodied her own treatise of life, which she shared with me often: “Think like a man. Work like a dog. And always be a lady.”

Until this day, I still considere New York and its art world a great shaper of my life, particularly in navigating volatile personalities. Hollis’s gallery was elegant and quiet, but it would teach me the art of hustle. It was there that I met Vivian, who would become a great teacher, my fuel to achieve excellence, and a reminder that hard work gets you a lot of places at the top of the Art World.

Vivian, part Cuban, was wonderfully attractive—dark skin, well-coiffed hair, red nails. She was also tough, militant, and a bit dramatic. (Unlike Hollis, who was gracious, calm, and wonderful still Southern, despite his time in New York.) Vivian moved at a fast pace, ordered the gallerists (on any level) to perfect their jobs, and pushed until we reached a height we didn't know existed.

I haven't seen or spoken to Vivan in over twenty years, but I learned my best lessons from her—such as not to be intimated by anyone, hire great people who are smarter than you, and allow staffers the freedom to grow. I also took away the thing I liked about her most: black leather pants. So anytime I am feeling low (regardless of the season), I sport those tight, hot bottoms and go kick some ass, remembering Vivian at the center of my passionate climb.

God, New York was phonology and culture war, applicable in all New York worlds, particularly its art scene. Molly was also an associate at the Hollist Taggart Galleries. She had Rapunzel-like hair, curly and dark. She was gregarious and wonderfully funny. She knew all the gossip and all the trashy love stories happening on the Upper East Side. She helped navigate the personalities and taught me the ins and outs of gallery dealing, auction dealing, and real life New York. We have remained friends and supporters for many years.

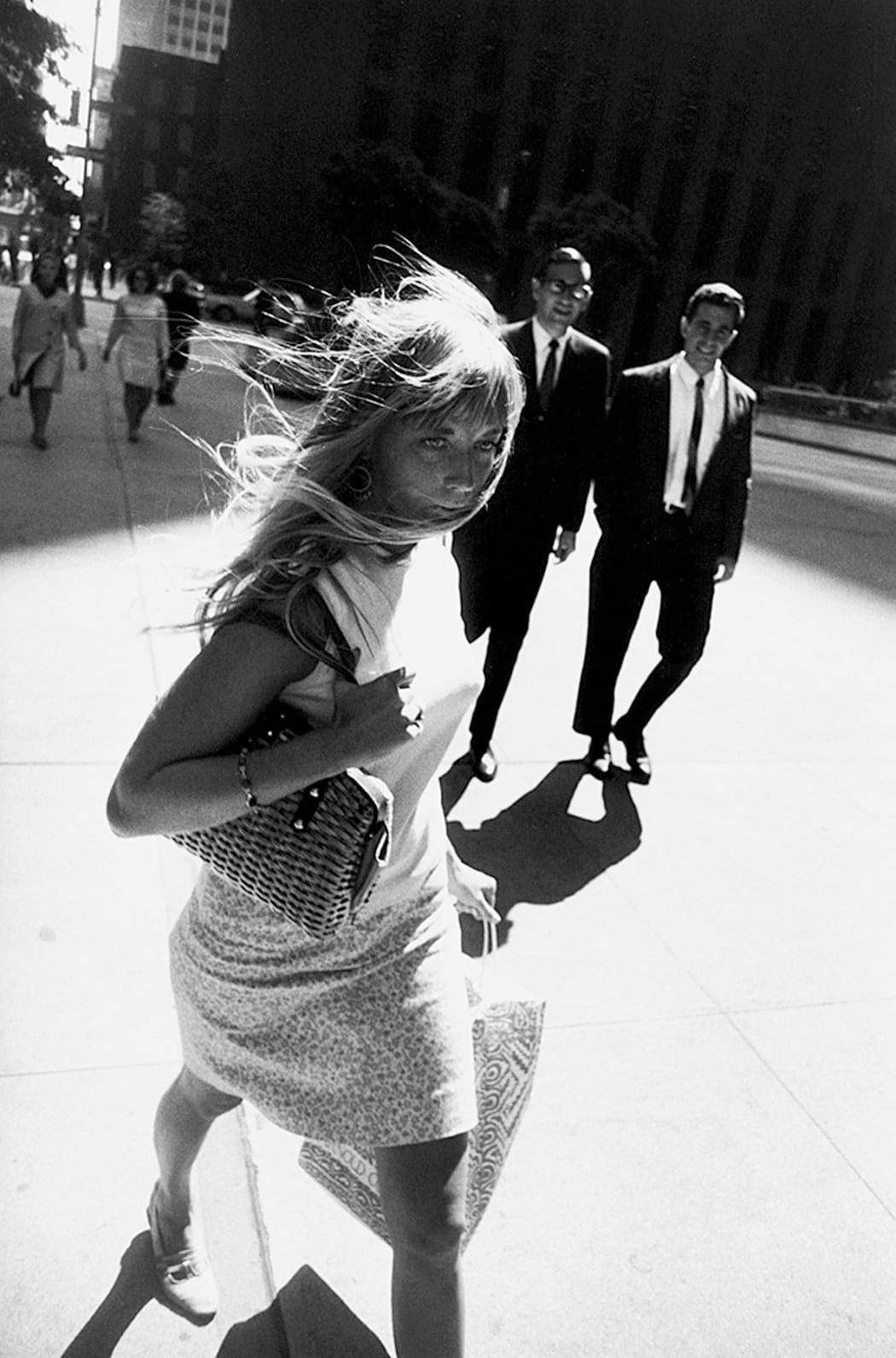

The sun always seemed greedy in New York City, choosing one side of the street to assault with sporadic bolts of light. In the winter, with long workdays, subway travel, and a dark return to a cramped apartment, it would be days before I’d see the sun. There were heat lamp treatments and tanning beds to help me through. It was a fault of mine to believe that every word and every motion had logic and fit into a neat, organized agenda. In New York, unpredictability ruled, and randomness became the norm.

I continued my mission to learn everything I could about fine art and photography. Weekend days, I would arrive at the Met early and stay until it closed, having lunch at the café and studying one section at a time. I love being around beautiful objects and learning the history and literature that go with them. I knew the guards and the staff. I was entranced by the black-and-white photographs by the Greats who had traveled the South, their oeuvres presented in THE Met: Walker Evans and Robert Frank, among others. As a student, I was given access to pull prints, and I was stimulated and in awe, pulling print by print in the photography room, abiding by the rules I so often break now (wear white gloves all the time, no lipstick, no candy, and pencil only). I’m such a rebel in this way. It was here that I first saw a vintage Robert Klein photograph—rich in color, dark in tone, and magical upon sight. In years to come, it would be the first photograph I would sell over $50,0000, an art dealer’s milestone. I also studied painters who had spent time in the South but made it in New York: Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, and Romare Bearden, among others. My feet—perpetually clad in leopard print boots with a short heel—would ache from standing and looking at art for hours on end. The only essence of a clock was when the janitors flooded into the museum, entering rooms after closing hours.

After some time in New York, I felt like I had exhausted my continued education in the visual arts. And on one particular night, smog veiled the canvas of stars, and the moon hung like a Christmas ornament in the center of the sky. It was an oddly quiet night in our tiny apartment, which seemed scaled to our small sizes. It was like a cocoon. I put down the book I was reading—it had grown cold inside—and then Mama called. Back in Mississippi, it was an appropriate spring day. My nephew Jacob was climbing trees, and my sister was gardening her hydrangeas.

Nestled in that tiny apartment, sipping bourbon and inhaling the moon pies Mama had been shipping in bulk while the spring snow continued to fall, I could no longer deny that the unsettled chill looming in my bones was more than unfriendly weather. I began to journal, rolling out the shadows of life, loss, and why I wanted to go home.

I shed New York like an old coat.

I returned home to Mississippi—forever the jewel in my heart. I arrived—and departed—with two tapestry suitcases, their contents from the beginning of the journey to the end the same. I came. I saw. I conquered. And I often think of that city, and my life there, in much the same way as the subway sign on Bleaker Street that read, “New York City: Comedy. Drama. Romance. Electrifying.”