There are decisions and circumstances in our lives that are true turning points, the yes and no so delicate that they lead us into a river flowing so aggressively in on direction that we can’t turn back. Two key decisions for me: not to marry a college sweetheart and not to pursue running my father’s furniture company, Jacob, Inc. To chart my own course, I had to make these choices about marriage, family , and career early. To think differently and do differently than many of my contemporaries was direct and conscious yet uncertain. These decisions were my tickets out yet would also raise many question marks and create some regrets over the years. I left the tribe and did not realize the impossibility of ever really returning. The circumstance? My father died.

Looking back over my shoulder, so much of the procurement in my life occurred in the compacted time of my senior year at Ole Miss and it has taken me years of couch sitting in my SueBella’s therapy office to process so much of it. That time is undoubtedly when my life shifted and my career as an art dealer began.

I was born and raised (with no margin for anything different) to attend one of the pilot schools—University of Mississippi or Mississippi State—and default into a top Greek house with large columns and grand doors. Marrying well was not discouraged. Rush started mid-high school and so much focus was on the right Greek house with rules like no drinking, sex, and dating the “wrong boy.” On weekends, we attended Ole Miss football games and rush parties at selected sorority houses on Sunday mornings, nibbling cheese straws and sipping lime punch from silver monogrammed cups.

Upon initiation, we were expected to wear white dresses and DDD pins (often accessorized by a sorority sister or dear friend of its sisterhood) and required to take courses on “manners and Southern behavior.” We learned how to set a formal dinner table, sit appropriately with ankles crossed and straight stiff backs, proper language when receiving a phone call. We also were handed a rule book noting that Tri Deltas were required to achieve a certain CPA and smoke sitting down, were prohibited from table or stage dancing (rules broken by most), and could not bring boys beyond the foyer or parlor (again, rules broken by most). If a boy and girl were to stay overnight together, may the two be married or forever hide her DDD letters.

Most rules seemed non-applicable on football weekends, as our housemother Ms. Julia took time away from the house to garden (and she didn’t want to be woken all hours by drunken stoppers and Hotty Toddy cheers). The Tri Delta house was a short stroll to the Grove, a tradition if not sacred ground for tail gating and Ole Miss talk and debauchery. Red solo cups were discorporate of liquor and mixers, no ice necessary and grabbing a needed chicken wing from a stranger’s table is acceptable.

I don’t know exactly how I flourished creatively in such a predictable and sometimes limiting environment. It was at times a seemingly rigid structure and a conventional circle of friends. Although I thrived and enjoyed much of my life as a Tri-Delta, I found most of my joys in my schoolwork—newly discovered art history classes, creative writing classes, English literature classes, and periodic painting class by the notable Mississippi painter Wyatt Waters on weekends. These were not only a source of sanity, but also a corridor to new worlds awaiting exploration.

This particular spring day, the Tri-Delta house held anxious sorority sisters as we prepared for the fall formal, typically celebrated on a steamboat on the Mississippi River. We would go by bus to Memphis and board there off the ramp downtown, viewing the bridge as we boarded.

The March day was intensely beautiful so most of us had our windows open. The breezy air, filled with the scent of honeysuckle and nearly bloomed blowers indigenous to Mississippi soil, whirled through the house, carrying the conversations more fluidly and expansively than usual. In most rooms I passed, sisters were walking around in their sequined or chiffon dresses, barefoot and unmade up—a dress rehearsal of sorts. A neurotic, academically charged student programmed by Daddy to attend law school after graduation, I had just dredged through one of my most intense test weeks. Having come out with all A’s, I was tired but glistening at my accomplishment. I couldn’t wait to share my success with my parents, gleaming on the other end of the telephone.

That phone call was a game changer, the shift. News from my camp was positive; new from home was devastating. Daddy was sick with cancer. Through the reassurances that he would be okay, I knew it would be a brutal and perhaps long fight. Not only was the emotional toll a heavy, and, at times, unbearable weight, but my set of responsibilities shifted dramatically. Overnight, I morphed from a college student focused on studies, sorority, LSAT preparation, and fashion picks for parties into my father’s rock and operation of business matters, family duties, death preparations, and medical bills. I’m often refereed to as an “old soul,” but the truth of the mater is that my twenties bought clarity of real life and real matters. It was the first time I realized the power of that cliche phrase “life or death.”

Yet through this time, I learned the art of unwavering focus and deception. Having read and article about Bill Clinton teaching himself to sleep only four to five hours a night, I began to trick my body into operating under the same deprivation. I learned to compact studying into the block of time between hospital visits and class. I also learned that tragedy projects uncertainty, heavy sadness, and fatigue so intense that you sleep in your clothes. I said no to a lot of experiences at Ole Miss, like parties and hangouts. I spent most of my time in libraries, hospitals, and my father’s store—a tripartite mix the was means to survival and keeping my family together. I still managed to make straight A’s—that small success would become a cornerstone of my life’s accomplishments. No matter the circumstances, my work and my mind are steadfast. I can always achieve and control there.

Certainly, there have been moments, particularly in the low times, when I questioned passing by men during that era of coming into my own. I have envied those with the big house in the suburbs, platoon of children, fancy cars with wood-grain dashboards, layered diamond rings (passed down generations), and country club memberships. But then it all seems so homogenized, and I think, had I chosen that, the only sanity—and one that would have eventually killed me—would have been large doses of bourbon.

In the next few months, doctors ran out of options, and we settled into the fat art Daddy wold die. That’s a hard bullet to bite for little girls who love their daddy, who grow up believing their daddy is invincible. My father and I spent a cold, rainy afternoon in early January, constructing his funeral, song by song, including scripture, guest list, and his suit and tie choice. He would have two services: the funeral at the Baptist church and the x in the Catholic Church. A rarity in the Southern Baptist services, an operatic Ave Maria was sung, and it’s the only thing I remember about the funeral. Ina. Clear indication of the level of respect the community had for my father, the local floral shops were so depleted that many gardeners allow their friends to choose for their foliage. Additional plants were shipped in from nearby Oxford, Mississippi and Memphis, Tennessee.

I buried my father on a Sunday; I was back in class on Monday, per my mother’s demand and my expectation of self. I walked from the Tri Delta House with my best friend Sarah to our creative writing class taught by the great writer, Larry Brown.

Larry Brown was a powerful voice in my final year year at Ole Miss, teaching me in creative writing class and Son, Joe, and Big Bad Love, a long with countless short stories. Had I not know Larry, my life would have been much different, and I don’t know if I would have had the courage to embrace my love affair with my career, my story, this book. During this trying and dark time, Larry’s class was an escape of sorts through reading assignments, writing short stories, and being among so many creatives who always saw the world in shades of grey. But I was also learning the tools to construct and devise a long piece of writing, a skill set that would help me cope with my reality, then and later on.

Larry’s class was a critical experience that had lasting and monumental impact. He always believed—and practiced in his own mastery of the craft—that you should write what you know, put trouble on the front page, and write (long I) like you talk.

Every day of class, he walked in a leather jacket, white T-shirt, and worn boots still dirty from the red soil…. —typical attire for a writer but not necessarily an academic. (His office on campus was a phone wrapped in its cord. “So nobody will bother me,” he smirked.”

He smelled of sweet, fading bourgeon and cigarettes (class started around 4:00 p.m.), went to the board, and book a piece of chalk to his liking, and wrote “S-T-O-R-Y.” Then he turned to the class and said, “If yo udon’t have the guts to show your guts, get out.” In the first few writing assignments, not noted my inability to do this.

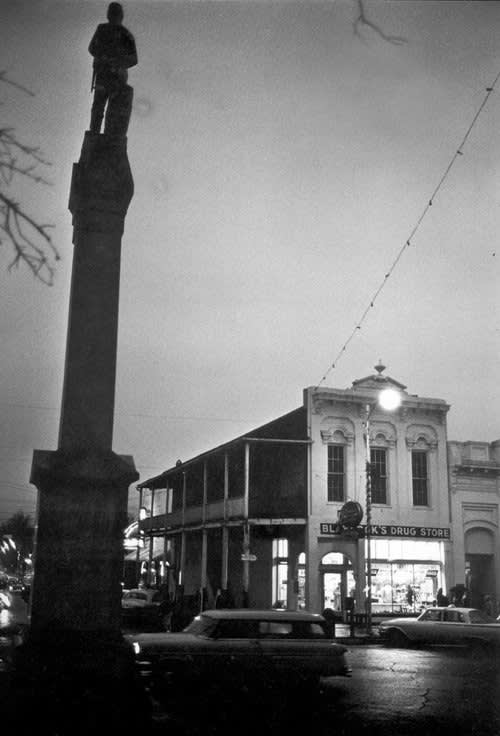

Larry, with a mere high school degree, wasn’t fond of an academic setting, so most of our classes were held at the City Grocery bar on the Oxford Square. Larry spent a lot of time at bars, as that’s where he “to most of his material.” “People act more natural to themselves in a bar,” he suggested. There, my classmates and I (many who have tone on to become acclaimed writers) talked about books, shared our stories, and, in many ways, learned to understand that our lives are, in their truest essence, stories. I set out to create and live mine.